Those of you who have been reading my weekly Black Coffee columns are aware of my repeated lamentations that, thanks to the manipulation of interest rates by the Fed and interventions and bail-outs by our federal government — which inhibit capitalism’s ability to eliminate dangerous market inefficiencies — price discovery is officially dead.

Instead of a free market, we have a quasi-command economy. In fact, it’s an economy consisting of a handful of Fed “economists” and academics who, after poring over reams of dubious government data, continually manipulate interest rates and the money supply. And that manipulation distorts the true price of everything from food to houses and stocks to bonds.

Of course, when it comes to determining prices, the decisions of a few central bankers can never be smarter than the collective wisdom of everyone participating in a truly-free market. But that’s the situation we’re stuck with today. As a result, we’re now suffering with a zombie economy on the verge of collapse.

So … how did we get to this point?

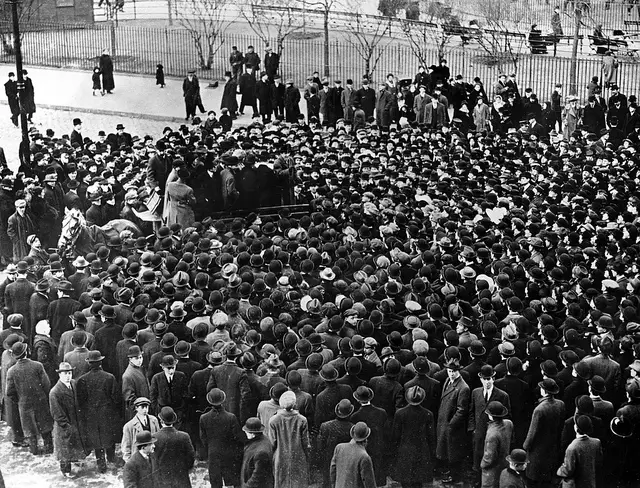

The Wisdom of Crowds

Well, I think the following story, excerpted from the book Other Peoples Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People? by John Kay, goes a long way toward explaining the process — and the wisdom of crowds – in a very entertaining and easy-to-understand way:

In 1906 the great statistician Francis Galton observed a competition to guess the weight of an ox at a country fair in which 800 people entered. Galton, being the kind of man he was, ran statistical tests on the numbers. He discovered that the average guess was extremely close to the true weight of the ox.

This story was told by James Surowiecki, in his entertaining book, The Wisdom of Crowds:

“Not many people know the events that followed. A few years later, the scales seemed to become less reliable. Repairs would be expensive, but the fair organizer had a brilliant idea. Since attendees were so good at guessing the weight of an ox, it was unnecessary to repair the scales. The organizer would simply ask everyone to guess the weight, and take the average of their estimates.

“A new problem emerged, however. Once weight-guessing competitions became the rage, some participants tried to cheat. They even tried to get privileged information from the farmer who bred the ox. But there was fear that, if some people had an edge, others would be reluctant to enter the weight-guessing competition.

“With few entrants, you could not rely on the wisdom of crowds. The process of weight discovery would be damaged.

“So strict regulatory rules were introduced. The farmer was asked to prepare three-monthly bulletins on the development of his ox. These bulletins were posted on the door of the market for everyone to read.

“If the farmer gave his friends any other information about the beast, that information was also to be posted on the market door. And anyone who entered the competition who had knowledge about the ox that was not available to the world at large would be expelled from the market. In this way the integrity of the weight-guessing process would be maintained.

“Professional analysts scrutinized the contents of these regulatory announcements and advised their clients on their implications. They wined and dined farmers; but once the farmers were required to be careful about the information they disclosed, these lunches became less useful. Some smarter analysts realized that understanding the nutrition and health of the ox wasn’t that useful anyway.

“Since the ox was no longer being weighed — what mattered were the guesses of the bystanders — the key to success lay not in correctly assessing the weight of the ox but in correctly assessing what others would guess.

“Or what other people would guess others would guess. And so on…

“Some people — such as old Farmer Buffett — claimed that the results of this process were more and more divorced from the realities of ox rearing. But he was ignored. True, Farmer Buffett’s beasts did appear healthy and well fed, and his finances ever more prosperous; but he was a countryman who didn’t really understand how markets work.

“International bodies were established to define the rules for assessing the weight of the ox. There were two competing standards — generally accepted ox-weighing principles, and international ox-weighing standards. But both agreed on one fundamental principle, which followed from the need to eliminate the role of subjective assessment by any individual. The weight of the ox was officially defined as the average of everyones guesses.

“One difficulty was that sometimes there were few or even no guesses of the weight of the ox.

“But that problem was soon overcome. Mathematicians from the University of Chicago developed models from which it was possible to estimate what, if there had actually been many guesses as to the weight of the ox, the average of these guesses would have been. No knowledge of animal husbandry was required, only a powerful computer.

“By this time, there was a large industry of professional weight-guessers, organizers of weight-guessing competitions and advisers helping people to refine their guesses. Some people suggested that it might be cheaper to repair the scales. But they were derided. Why go back to relying on the judgment of a single auctioneer. Especially when you could benefit from the aggregated wisdom of so many clever people?

“And then the ox died. Amid all this activity, no one had remembered to feed it.”

Folks, this is an almost-perfect analogy for how we determine prices in today’s “free” markets. Or should I say “mispriced.”

We’re just waiting for the ox to finally kick the bucket.

Photo Credit: Kheel Center, Cornell University

Question of the Week